Writing in Risk and Blame: Essays on Cultural Theory, anthropologist and sociologist Mary Douglas expressed the importance of recognising one’s own biases, the importance of reflexivity.

‘My own preference has emerged as an idealized form of hierarchy. This has always given me to some degree the professional advantage of feeling out of kilter with the times. It gives me a standpoint from which to see that in this 300-year expansionary trend of Western civilization two kinds of cultures have come to dominate, two that are opposed to hierarchy. Today I am arguing that unless we learn to control our cultivated gut response against the idea of hierarchy we will have no choice among models of the good society to counter our long-established predatory, expansionist trend. By sheer default, among cultural forms hierarchy is the rejected Other. We take it for granted that hierarchy will always fall into traps of routinization and censorship; we see its dangers but have no clear model of how it would be if it worked well. Yet hierarchy is the social form that can impose economies, and make constraints acceptable.’ (Douglas 1994:266).

This use of Cultural Theory as a tool for reflexivity is laudable. How does this particular passage make the reader feel – comfortable, or uncomfortable? Perhaps that’s a measure of how far one agrees or disagrees with a hierarchical world view or cultural bias.

Myself, I’m squirming. Especially when Douglas speaks of ‘imposing economies’ and ‘making constraints acceptable’. If these are hierarchy’s trump cards, I’m playing the wrong game. It is not ‘by sheer default’ that the shortcomings of hierarchies have been highlighted. There really are some serious shortcomings.

For the targets of Douglas’s criticism, Egalitarianism and Individualism, it can hardly be said we need more hierarchy, greater bureaucratization, more red tape, a renewed emphasis on distinctions between races, genders and classes, stronger, more ordered leadership. The idea that Egalitarianism is one of the two kinds of cultures that have come to dominate is laughable. If only that were true!

But looking through the four-faceted prism of cultural theory, instead of through the Egalitarian face alone, enables a wider view. This fourfold vision (to quote William Blake, quite out of context) enables an understanding that:

- the opinions I tend to express are just the sorts of thing I would say, as though they had been scripted in advance;

- my own cultural preferences have indeed made great and lasting inroads into Western society, many of which I simply take for granted;

- if I want to convince people, or connect with them, I need to recognize the seriousness of other perspectives. Other people aren’t stupid or wilfully unobservant. But they may have a different cultural preference with its concomitant axioms and norms.

- Douglas does have a point about Hierarchy – as we set about destroying the bastions of unearned privilege and discrimination in the name of freedom (the Individualist slogan) and equality (the Egalitarian mantra), we do indeed hardly pause to consider what Hierarchy might look like ‘if it worked well’. Perhaps we should. There’s a warning in Douglas’s work that we may be ‘throwing out the baby with the bathwater’. Well, maybe, just maybe, we are.

But…

The passage begs a few questions. It’s interesting that Douglas uses her Cultural Theory to characterise an historical trajectory. She is telling a story here about the sweep of centuries. ‘in this 300-year expansionary trend of Western civilization two kinds of cultures have come to dominate, two that are opposed to hierarchy’. It’s highly suggestive, a bit like Habermas’s tale of the detachment of the Lifeworld from the System, or like one of Foucauld’s genealogies. But there’s a need to be careful with such sweeping historical retellings. If the theory offers a perspective to help explain the temporal trajectory of a civilization, one cannot then also work the other way around and use the history to ‘prove’ or ‘demonstrate’ the theory…

Then there’s the question of balance. Durkheim and the founders of modern Sociology imagined society to be in equilibrium. Many economists still do. They worried about the forces that threatened to unsettle this eirenic scene. Underlying Douglas’s conception of society too is a concern that things have become unbalanced somehow. With Hierarchy in retreat, what could possibly counterbalance ‘our long-established predatory, expansionist trend’? Well, one answer would be: nothing! We’re all going to hell in a handbasket! But who says society actually is a balanced system? It’s all just a metaphor. So we could as well say, as some now do, that the social world can be better characterised as being in dynamic disequilibrium, that tension and unbalance is the order of the day. If this were the case, the demise of Hierarchy, or one of the other cultural biases, is just the kind of thing we might expect to happen from time to time, and yes, it would be unsettling, but not necessarily disastrous. It’s hard to think about this, since our cultural biases predispose us to privilege different trajectories. Hierarchy would of course prefer an equilibrium that required careful management, while Individualism might be more enthused by a bit, or even a lot, of creative destruction.

Mary Douglas may have been ‘wrong’ in the sense that her position in favour of an ‘idealised form of hierarchy’ may be critiqued by those who don’t share it. But she was surely very right to recognise that we do have cultural biases, and that recognising them and owning them is the first step to transcending them.

Now read:

some recent applications of Mary Douglas’s theories to contemporary concerns.

Interview with Mary Douglas.

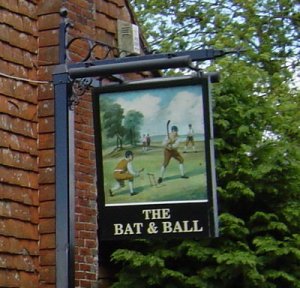

Fascinating uses of Mary Douglas’s cultural theory pop up every so often. The latest relates to the venerable game of cricket.

Fascinating uses of Mary Douglas’s cultural theory pop up every so often. The latest relates to the venerable game of cricket.